The Pulse on Perfusion: Color Vision, Readiness, and the Path to Perfusion School

Selecting candidates for perfusion school takes more than strong academics. Programs look for emotional readiness, good judgment, and the ability to stay calm under pressure. This month’s Pulse on Perfusion poll asked practicing perfusionists and other professionals across the field to share their views on what prepares someone for training, including how they think about color vision in the admission process.

Disclaimer: The information in this post reflects the views and experiences shared by survey respondents and is provided solely for general education and discussion. Perfusion.com does not endorse or adopt any of the opinions, conclusions or preferences expressed in the survey results. Nothing in this post should be interpreted as establishing admissions standards, employment criteria or clinical requirements for any program, hospital or organization, nor as suggesting that color vision differences or any other condition limit an individual’s ability to enter or practice in the perfusion field. All discussions should be understood within the framework of full compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and all other applicable laws requiring reasonable accommodation and nondiscrimination. Clinical practices, equipment and training methods vary, and readers should consult their institution’s policies for specific guidance.

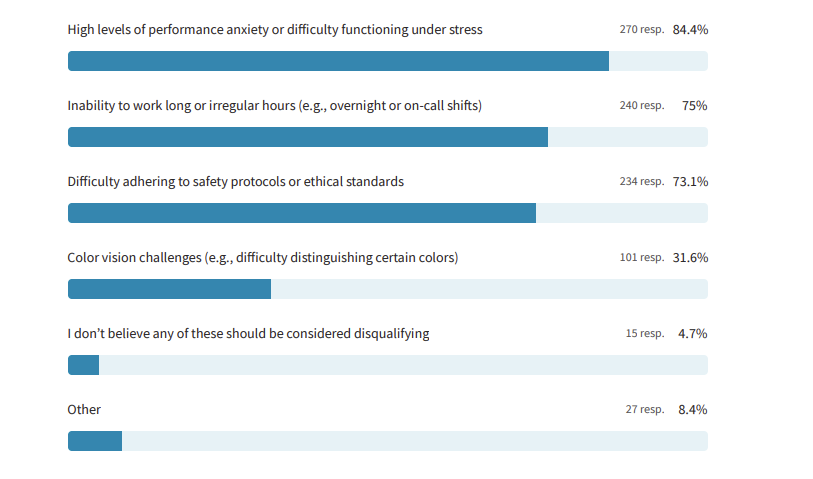

Question 1: What factors do you believe should be carefully considered when evaluating readiness for perfusion school?

- High levels of performance anxiety or difficulty functioning under stress – 84.4%

- Inability to work long or irregular hours (e.g., overnight or on-call shifts) – 75%

- Difficulty adhering to safety protocols or ethical standards – 73.1%

- Color vision challenges (e.g., difficulty distinguishing certain colors) – 31.6%

- I don’t believe any of these should be considered disqualifying – 4.7%

- Other – 8.4%

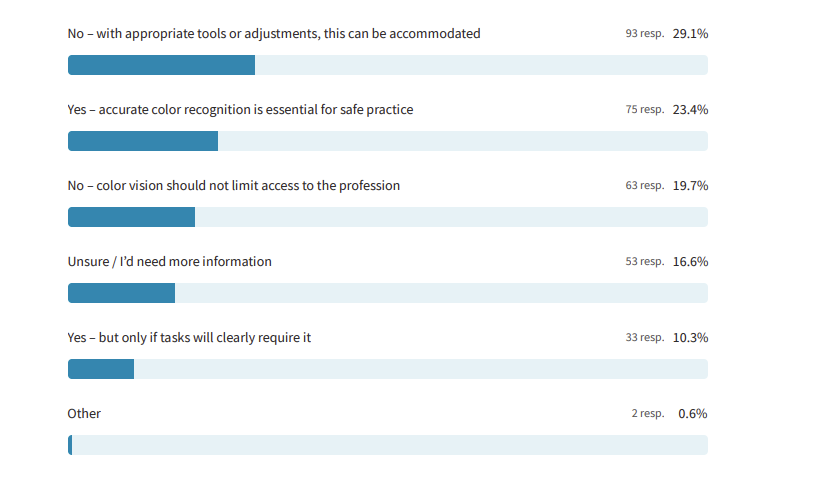

Question 2: Should color vision testing be part of the admissions process for perfusion programs?

- No – with appropriate tools or adjustments, this can be accommodated – 29.1%

- Yes – accurate color recognition is essential for safe practice – 23.4%

- No – color vision should not limit access to the profession -. 19.7%

- Unsure / I’d need more information – 16.6%

- Yes – but only if tasks will clearly require it – 10.3%

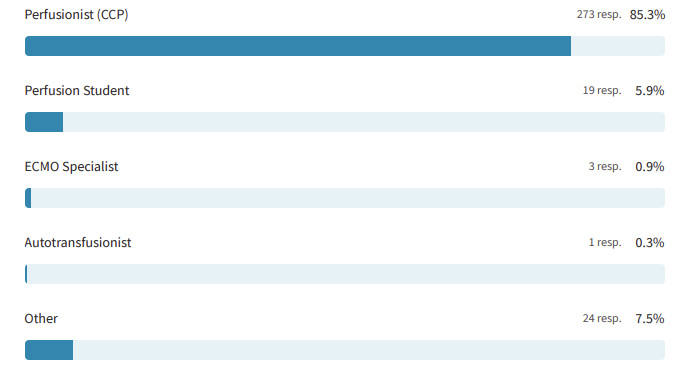

Most respondents were Certified Clinical Perfusionists (85.3%), lending the data the weight of lived experience in the OR. Another 5.9% were perfusion students, offering a glimpse into how emerging professionals view readiness, while 7.5% identified as “Other,” many of whom plan to enter the field.

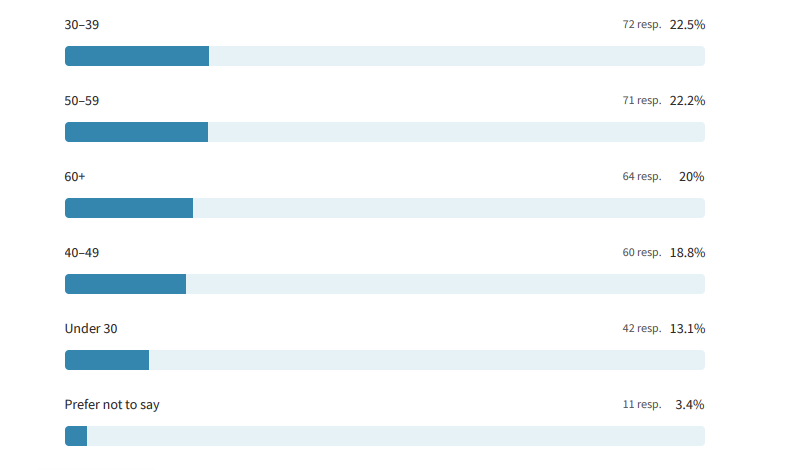

Age distribution revealed a remarkable balance across generations: 30–39 (22.5%), 50–59 (22.2%), and 60+ (20%). This mix created not just a diversity of opinions, but a dialogue between eras: from those navigating new technologies and changing admission standards to those who trained when mentorship and manual precision were the cornerstones of perfusion education. The result is a conversation that bridges tradition and innovation, where experience meets aspiration, and evolving definitions of readiness reflect how the field itself continues to grow.

Evaluating Readiness for Perfusion School

Determining readiness for perfusion school means balancing cognitive, emotional, and physical capabilities – traits that predict how well a student will perform under the intense and unpredictable conditions of the operating room. The options presented in Question 1 were designed to reflect real-world stressors and decision-making challenges faced in training and clinical environments.

Stress and Emotional Resilience

The top-ranked factor – high performance anxiety or difficulty functioning under stress (84.4%) – points to the emotional demands of perfusion work. Students entering the field must be prepared to think critically while managing life-and-death situations in real time. As one respondent shared:

“Psychological, emotional, and physical fitness are essential. You can’t hesitate when the patient’s life is literally in your hands.”

This consensus underscores the profession’s recognition that technical proficiency alone isn’t enough. Emotional stability, mental endurance, and self-awareness are key predictors of long-term success in perfusion school and beyond.

Workload, Ethics, and Endurance

Next, 75% of respondents cited inability to work long or irregular hours as a readiness concern. Perfusionists often manage extended procedures, on-call shifts, and emergency interventions – conditions that can challenge even the most disciplined professionals. Respondents stressed that applicants must understand these realities early:

“Work ethic—understanding you may work long hours, odd shifts, holidays, weekends, during family birthdays, functions, etc.,” one wrote.

Closely linked, 73.1% also emphasized the importance of adhering to safety protocols and ethical standards. This reflects the profession’s emphasis on accountability and integrity, especially in roles where decisions directly impact patient outcomes.

Beyond the Checklist

While fewer respondents (31.6%) identified color vision challenges as a significant readiness factor, open-ended comments in the “Other” category broadened the conversation. Participants cited qualities like motivation, emotional maturity, common sense, and teamwork as equally important. One respondent wrote:

“Taking ownership of the tasks and cases, not being lazy or cutting corners, apathy and leaving the work for someone else to do is ruining this profession.”

Another pointed to physical and cognitive skills often overlooked:

“Ability to orient and move in space and time, understand orders, and coordinate hand-eye movements.”

Together, these insights suggest that readiness for perfusion school extends beyond aptitude tests. It’s about cultivating professionalism, empathy, and resilience in future practitioners.

Color Vision Testing: The Case Against

Responses to Question 2 revealed that 48.8% of participants did not support mandatory color vision testing in perfusion school admissions, with most noting that any visual challenges can be accommodated through training or technology.

For these respondents, adaptability – not visual perfection – defines clinical readiness:

“Color-blind people can still see shades and contrast, and there are enough safety features to alert changes in blood oxygenation,” one shared.

Another added:

“Color vision issues can be accommodated and are not detrimental to patient safety. If a colorblind individual can make accommodations in perfusion, I would already consider them a critical thinker and that would be an asset on any team.”

Many emphasized that reliance on color alone can be risky:

“Only relying on a color difference for something safety-related isn’t safe. It’s lazy. It can be a redundancy built into the system, but should never be the first line to protect a patient.”

Some offered firsthand insight:

“I am color blind and have been a CCP for 21 years,” one respondent noted.

Such perspectives suggest that clinical performance depends more on training, awareness, and system safeguards than on any single sensory ability.

Color Vision Testing: The Case For

Conversely, 33.7% of respondents believed color vision testing should play a role, either universally or in cases where tasks clearly require it. For this group, the issue was not about exclusion, but about ensuring safety in environments where quick visual interpretation can be life-saving.

“If someone is color blind, I don’t think that should exclude them,” one respondent wrote, “but they need to be aware of accommodations that they and other team members will need in reference to the monitor, blood color change, etc.”

Others stressed the role of color as a vital indicator:

“Oxygen analyzers are not standard operating equipment at every hospital. Older pumps do not have FiO₂ alarm capability. Not every program utilizes an inline ABG monitor (such as CDI). Recognition of color change in lines can be the only indicator of lower pO₂ for a couple of minutes. This can be especially true during ECMO transports using oxygen cylinders.”

Another summarized the concern simply:

“Determining color change between oxygenated blood is a common practice in perfusion. It’s imperative a perfusionist can quickly and accurately determine if patient blood is oxygenated.”

Supporters of testing did not dismiss accommodation but viewed baseline awareness of color cues as an additional safeguard for patients, especially in situations where technology may fail or time is critical.

A Note on Inclusivity and Perspective

While the conversation around color vision prompted diverse opinions, many respondents were careful to emphasize that inclusion and safety must coexist. The discussion was not about exclusion but about awareness – how training programs can responsibly prepare all students, including those with sensory differences, through adaptive technologies, communication strategies, and standardized procedures.

This poll underscores that readiness for perfusion school should be assessed with both empathy and equity in mind. By fostering a culture of openness and reasonable accommodation, the perfusion community can continue to evolve while ensuring that opportunities remain accessible to all who meet the profession’s demanding standards.

Reflections on Readiness and the Future of Perfusion School

This month’s Pulse on Perfusion captured a profession reflecting deeply on what it means to be “ready” for the journey into perfusion. From emotional composure and endurance to ethical consistency and sensory awareness, respondents articulated a multidimensional view of readiness – one that values both skill and character. The dialogue surrounding color vision reflects a broader truth: that excellence in perfusion arises not from uniformity, but from collaboration, awareness, and accountability. By continuing to discuss these issues with care and respect, the field moves closer to a shared vision of education that is rigorous, inclusive, and responsive to the realities of modern healthcare.

Appendix of Additional Insights

General Trends by Age Group

- Under 30: Emphasized adaptability, technology, and motivation as equal to sensory ability.

- Ages 30–39: Balanced stress tolerance with inclusivity, reflecting early-career adaptability.

- Ages 40–49: Prioritized ethics, responsibility, and composure – qualities often learned through experience.

- Ages 50–59 and 60+: More likely to support testing when tied directly to patient safety but recognized the value of teamwork and clinical judgment as compensating strengths.

Key Correlations Between Readiness and Color Vision Opinions

- Opponents of color vision testing often highlighted technology, monitoring systems, and collaboration as reliable safeguards.

- Supporters most often cited blood color differentiation and visual cues during bypass and ECMO as reasons for testing.

- Across all groups, the takeaway was consistent: success in perfusion school is rooted in resilience, critical thinking, and the ability to adapt – traits that go far beyond what the eye can see.