The Pulse on Perfusion: AI, Accountability, and the Role of the Perfusionist

At Perfusion.com, we believe that dialogue drives progress, and our monthly poll series continues to reveal just how thoughtful, passionate, and engaged this professional community is. These quick polls give voice to real perspectives and offer a window into the evolving challenges facing perfusion today.

This month’s topic took us into complex – and sometimes controversial – territory: artificial intelligence. Specifically, we explored how AI might influence medical error rates and who should be held accountable if something goes wrong.

Poll Results at a Glance

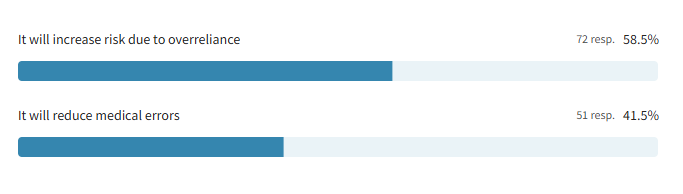

Question 1: Do you think the use of AI in perfusion will reduce medical errors or increase the risk due to system overreliance?

- It will increase risk due to overreliance – 58.5%

- It will reduce medical errors – 41.5%

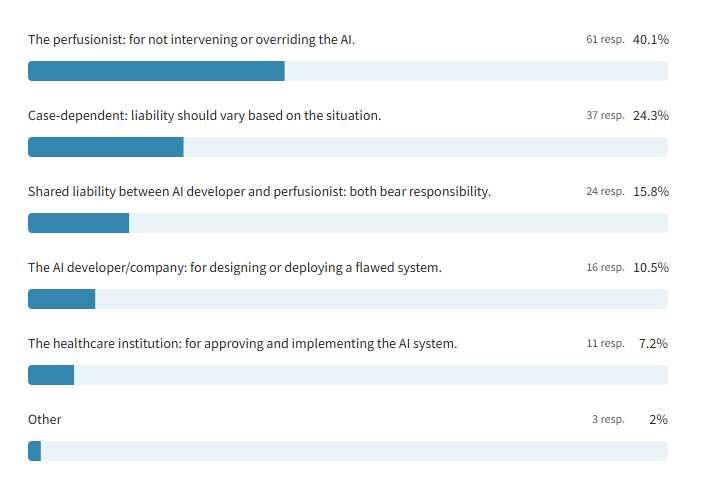

Question 2: If an AI system makes a harmful decision during bypass and a perfusionist was monitoring, who should be held liable?

- The perfusionist: for not intervening or overriding the AI – 40.1%

- Case-dependent: liability should vary based on the situation – 24.3%

- Shared liability between AI developer and perfusionist – 15.8%

- The AI developer/company – 10.5%

- The healthcare institution – 7.2%

- Other – 2%

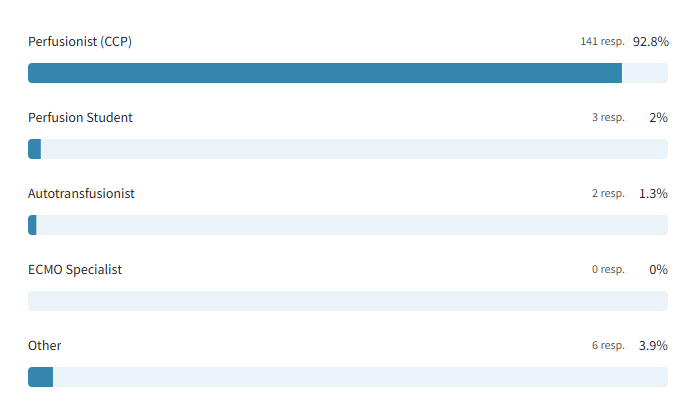

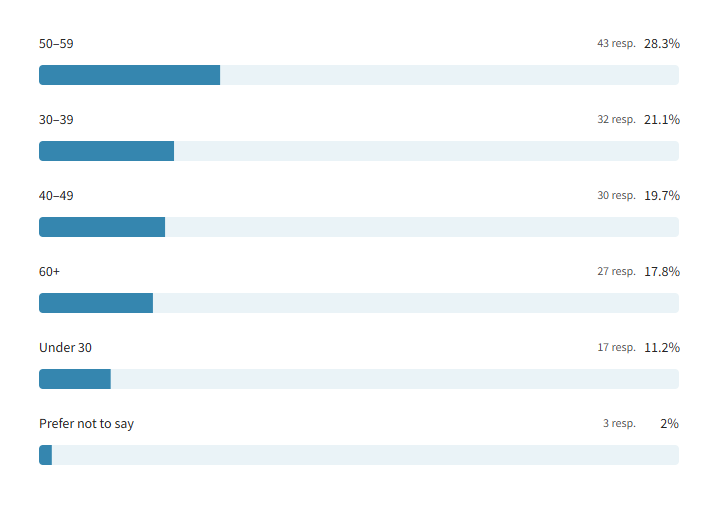

This snapshot reveals a profession deeply engaged in conversations around technology and accountability. Most respondents were practicing certified clinical perfusionists (92.8%), with insights coming from a wide range of experience levels. The age distribution leaned toward mid- and late-career professionals, with the largest segments in the 50–59 (28.3%) and 30–39 (21.1%) age groups, highlighting a discussion shaped by both seasoned perspectives and emerging voices in the field.

Profession:

Age Demographics:

Balancing Promise and Risk: AI in Perfusion

When asked whether the use of AI in perfusion would reduce medical errors or increase risk due to system overreliance, the majority of respondents (58.5%) expressed concern that AI could do more harm than good. Many felt that technology, while potentially helpful, should never be trusted to act autonomously in life-or-death scenarios. Reliability, clinical oversight, and the unpredictability of technology in high-pressure moments were recurring themes.

As one respondent cautioned:

“Having a system that is solely AI/electronically generated is an increase in risk in itself. We all know that tech can be useful to some extent, but I think relying on it to perform life-saving measures would be risky. As the tech could glitch or freeze up, and the risk of that happening while trying to keep a patient stable is far too risky in my opinion.”

Some respondents dismissed the concept entirely, while others stressed that its usefulness would depend on maintaining human authority over clinical decision-making.

At the same time, a significant 41.5% of respondents expressed optimism that AI could help reduce errors, enhance safety, and serve as a valuable clinical tool. While most in this group did not elaborate on their selection, their alignment with the idea of AI as a supportive resource, not a replacement, surfaced more strongly in the context of the second question on liability. This suggests that even among AI’s supporters, there is a clear expectation that technology should complement, not replace, the expertise of the perfusionist.

Who’s at Fault When AI Fails? The Debate Over Accountability

While opinions varied on whether AI will help or hinder perfusion outcomes, respondents were even more vocal when it came to accountability. If an AI system makes a harmful decision during bypass, who is ultimately responsible? The answers revealed a strong consensus around clinical oversight, but also pointed to deeper questions about system design, institutional responsibility, and the boundaries of technology in patient care.

Responsibility Matters: “The Perfusionist Should Be Held Liable” – 40.1%

For many respondents, the introduction of AI into the operating room does not change one fundamental truth: the perfusionist is responsible for patient safety. This viewpoint – shared by 40% of participants – reflects a deep commitment to clinical vigilance, regardless of the tools being used.

As one respondent put it:

“Total vigilance from [the] perfusionist is the core reason for being behind a pump. [The] system has to have the capability of perfusion intervention; otherwise, do not approve of the system.”

Here, technology is not seen as inherently flawed, but its value depends entirely on the perfusionist’s ability to step in, override, and redirect care when necessary.

Others framed AI as just another tool that demands proper training and real-time judgment:

“AI is like any other advanced new technology used by the perfusionist, where training, competencies, skills, and safety are very important, though the perfusionist must predict and interfere at the right time before any risk or incident happens.”

For this group, accountability can’t be automated. The perfusionist remains the final decision-maker because machines can assist, but only humans can be held responsible.

Looking at the Nuance: “Case-Dependent” – 24.3%

Nearly a quarter of respondents felt that liability in an AI-related error can’t be assigned in blanket terms; it depends on the situation. These perfusionists called for a more individualized approach that accounts for context, system design, and the level of human oversight involved.

“I don’t believe that there is a one-size-fits-all answer. I think it depends on the AI model implementation as well as how much oversight the perfusionist has… how could this have been prevented, and which actions would have needed to take place or be amended?”

Another respondent offered a clear and practical illustration of this perspective:

“It’s case by case. Situations are different. For instance, if the pump goes wrong, that’s the manufacturer’s responsibility.”

While their responses varied, the core message was consistent: accountability in the OR is complex, and the right answer often lies in the details.

Split Responsibility: “Shared Liability Between AI Developer and Perfusionist” – 15.8%

A smaller but significant portion of respondents took a balanced view, arguing that both the perfusionist and the AI developer should bear responsibility when something goes wrong. This group acknowledged the clinician’s duty to monitor and intervene, but also pointed out that flawed tools shouldn’t be exempt from scrutiny.

“When AI is being sold as a tool for perfusion and it falls short of its function, there has to be liability with the developer. As the Perfusionist, there is liability there as well. That’s the sole responsibility of the perfusionist: to maintain CPB without the use of AI.”

Many in this group saw the perfusionist as the operator and final decision-maker, but felt that manufacturers share responsibility for ensuring their systems perform safely and as advertised.

One respondent reflected on how their view evolved:

“I originally wanted to go with the Perfusionist taking sole responsibility. However, after seeing the options, I think a slightly more nuanced approach is desirable. The AI manufacturer deserves some blame, but I’m mostly taking some liberties and considering the situation as a “perfusionist” in that role being someone who is trained either on the job or in school to operate the specific AI. So, just like any other position operating computer software or a machine, the user has to be the one to take the majority of the blame, I feel. Again, simply viewing it as an operator not being able to manage their machine/software.”

This perspective reinforces a key theme: while clinicians must remain in control, they should not carry the entire burden when using complex tools designed and sometimes mandated by others. Responsibility, like the technology itself, is shared.

System Error: “The AI Developer Should Be Held Liable” – 10.5%

A smaller but resolute group of respondents placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of AI developers. For these participants, if a system is flawed, untested, or permitted to make autonomous decisions, then the liability belongs with those who created it.

“AI should be so well tested that the company providing it assumes responsibility.”

This group emphasized that AI tools used in critical care settings must meet the highest standards because when lives are on the line, failure isn’t just a technical glitch; it’s a systemic error.

“AI is a system. In case of harm, it means that the system is flawed.”

A respondent warned against giving AI too much authority without oversight. If a tool is capable of making decisions without the clinician’s input, then it begins to take on a clinical role, one it was never trained or licensed to hold.

“Regardless of the error made, if AI is allowed to make decisions without approval from the perfusionist, then the AI developer should be held liable because it is acting as a clinician.”

In their view, liability should follow agency. And if AI is granted autonomy, so too must it bear responsibility.

Institutional Oversight: “The Healthcare Institution Should Be Held Liable” – 7.2%

A smaller group of respondents pointed to a different source of accountability: the healthcare institutions that implement AI systems. For these individuals, the responsibility lies not just with those who develop or use the technology, but with the organizations that approve it, deploy it, and set the protocols for its use.

“Decision makers have the authority to avoid this.”

These respondents stressed that hospitals and administrators are not passive players; they actively choose which systems to trust and integrate into patient care. With that authority, they argued, comes liability.

“I assume the hospital has done their due diligence on the capabilities of the AI system.”

From this perspective, institutions are expected to vet, test, and regulate the tools they put into clinicians’ hands. If something goes wrong, it may be a sign not just of user error or technical failure, but of flawed decision-making at the organizational level.

Beyond the Checklist: “Other” – 1.4%

A small number of respondents selected “Other,” offering thoughtful perspectives that didn’t fit neatly into a single category. Rather than assigning blame to one party, these individuals highlighted the complexity of shared responsibility and the importance of collaborative planning.

One respondent emphasized the need for proactive partnerships between clinicians and institutions:

“The approach should be case-dependent; liability should vary based on the situation. It starts with the healthcare institution working alongside a perfusionist to develop a plan that limits the reliance on artificial intelligence (AI) to prevent complications while prioritizing patient safety.”

Another took a broader view, pointing out that the scale of AI-related errors may extend beyond individual roles:

“Either everyone is liable or no one is. One can’t bear sole responsibility over something this big.”

A Profession in Conversation: Final Thoughts on AI in Perfusion

This month’s poll sparked one of the most layered and thought-provoking conversations yet. From firm stances on personal responsibility to nuanced takes on shared liability, respondents didn’t hold back, and the result is a compelling snapshot of a profession wrestling with rapid technological change. AI may be the topic, but what emerged was a deeper dialogue about trust, accountability, and the human element at the heart of perfusion.

Stay tuned for the next poll and blog, where we’ll continue amplifying your voices and perspectives!

Appendix of Additional Insights

General Trends by Age Group

- Younger Respondents (Under 30)

- 58.8% believe AI increases risk

- Only 17.6% believe it reduces errors

- Most selected “case-dependent” or shared/system-level liability

- 0% assigned blame to healthcare institutions

- Indicates skepticism of AI and openness to nuanced accountability

- Ages 30–39

- Most split group: 41.9% say AI increases risk, 32.3% say it reduces errors

- Most likely to hold the perfusionist liable (45.2%)

- Also open to institutional and shared responsibility

- Suggests a balanced view: cautious but not dismissive

- Ages 40–49

- 42.9% say AI increases risk, 35.7% say it reduces errors

- Favored clinician accountability more than any other group (50%)

- Low support for case-dependent or shared liability

- Reflects a strong emphasis on clinician responsibility

- Ages 50–59

- 51.2% believe AI increases risk (second-highest overall)

- Lower perfusionist blame (34.1%), higher shared/developer blame (36.6%)

- Few blamed institutions (2.4%)

- Indicates a critical view of AI systems and a strong focus on tool quality

- Ages 60+

- 46.2% believe AI increases risk, 38.5% say it reduces errors

- Even split between perfusionist (34.6%) and case-dependent (30.8%) responses

- Shows openness to AI, tempered by a desire for clinical discretion

Key Correlations Between AI Views and Liability Beliefs

- Trust in AI tends to shift accountability toward clinicians.

- Of those who believed AI would reduce medical errors, 53.1% still placed liability on the perfusionist.

- This suggests that even AI supporters see it as a tool, not a replacement, and believe the human operator must remain in control.

- They may trust AI to perform well, but not well enough to excuse clinical inaction.

- Skepticism of AI aligns with calls for shared or external accountability.

- Among those who chose shared liability, 69.6% believed AI would increase risk.

- Similarly, 62.5% of those who blamed the AI developer also believed AI would increase risk.

- This reflects concern that flawed technology introduces risk, and those who design or promote it should share the consequences.

- Those uncertain about AI tend to favor case-by-case evaluation.

- For respondents who selected “case-dependent”:

- 41.7% said AI increases risk

- 33.3% said it reduces errors

- 25% didn’t answer Question 1 at all

- This group may be cautious or undecided about AI’s safety and prefer flexibility in how responsibility is assigned.

- Their mixed responses suggest an openness to evaluating liability based on situational factors, not just fixed roles.

- The more blame placed on systems or institutions, the less trust in AI.

- Those who held AI developers or healthcare institutions responsible were the most skeptical:

- Over 60% in both groups said AI increases risk.

- Fewer than 20% said it reduces errors.

- These responses reflect a deeper mistrust of AI integration at the structural level, where poor implementation or oversight is seen as a root cause of harm.