ICPB: A Stroke Window

The 1st Stroke Window …

Gauging & Avoiding & Being Smart About it…

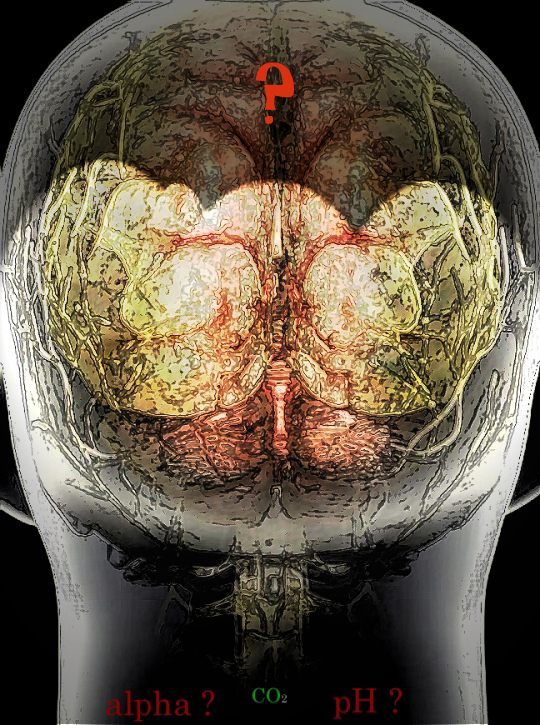

Bump up the age, notice the increased cerebral vascular issues, mix in a low body weight, a little calcium (in terms of deposits- here and there), a stiffened aorta, a low hemoglobin, and perhaps a significant hemodilutional drop once on bypass, and you have a recipe for a big dip in perfusion pressure / flow to vital parts of the head.

ICPB (Initiation of Cardiopulmonary Bypass)

On bypass and there you have it. The instant insult of hemodilution in tandem with 1% or greater Forane via vaporizer (dumps the pressure down).

There are many things that occur simultaneously as the patient’s blood transfers from it’s own delivery system to ours. The heart is evacuated of volume, it is empty and beating. Baroreceptor responses, and catacholamine releases are unpredictable in terms of hemodynamic response, and seem to always respond at 90 seconds to 3 minutes. The only thing that is truly predictable is that the patient’s pressure will drop once on bypass.

The immediate pressure drop assuredly addressed with neo- (bumps the pressure up…) drop flow- cross clamp on- cardioplegia delivered and you are on bypass at a cardiac input of 1.8 or higher, cooling as you go.

At two minutes you should be OK- barring any viscosity mediated hypotension issues.

But it is THAT window, the narrow transition from inception of bypass- arresting the heart- delivering your preliminary cardioplegia arrest dose, and drawing your first confirming lab at 10 minutes into the procedure that always gives me pause. Add it up- it’s roughly 0-10 minutes. Anoxic cells can die in that time period.

When was the last time you held your breath that long?

Transfusion Threshold ?

We are all over it when it comes to cost containment, 3 star STS ratings, and the lowest blood transfusion stats on the proverbial block. Right?

Those numbers might seem respectable, but then again, the troubling fact that raises it’s ugly head, is what does that represent in terms of patient outcome, the assumed moral moral obligation to the welfare of your patient?

Do you have the personal fortitude to put yourself out on a limb and push the issue of a perceived need for transfusion- regardless of the implied criticism or general reluctance- “the wait and see” attitude” ?

It is a fine line when debating the captain(s) of the ship, but clearly the need to enunciate an unpopular position must be followed through to it’s conclusion- if you are indeed an advocate for a positive outcome. That doesn’t suggest that the people you are discussing it with have no regard or anticipation of the patient’s condition through the course of bypass and further down the road.

Clearly they do- by academic rank and professional experience.

Transfusion has it’s own measurable impact on morbidity and mortality, that is undeniable and in the forefront of the minds of the surgeons and anesthesiologists we work with. So it becomes a delicate balance of delivering a concise plan and the ability to not step on toes.

In my opinion, transfusing a patient is an art.

The bottom line that you are dealing with, is that no one wants to do it. It affects the numbers, and becomes a hard sell.

The trigger point, and when to pull it is one of the defining moments of a pump run, and eventually it becomes a “gut feeling” in tandem with a well defined strategy.

What are Your Thoughts?

How to figure- The Trigger-

- Age

- Weight

- Gender

- Cerebrovascular Disease

- Baseline Hgb

- Prime Volume

- Depth of Hypothermia- and speed of onset

- MDA Habits (moderating pressures & pharm.)

- Length of Pump Run

Typically when I start my day- the first thing I do before I set up an ECC circuit is match the oxygenator to the patient’s body habitus. (That’s usually a phone call away- or a quick walk to preop holding)

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to recognize “small”. So then the evaluation process begins.

Age is a big thing, and gender perhaps more important. The totally key factor is factoring in the patient’s size to the equation and then asking myself a couple of simple questions.

- Will the patient most likely be transfused during their hospital stay?

- At arrival to ICU- is the Hgb likely to be less than 8.0 gm/dl or so?

- Will the Hgb drop below 7.0 gm/dl when I first go on?

If the answer is YES to either one of the above questions- well the transfusion torch is lit.

If that is the case, I will usually dump 1 (most often 2) units in the prime, add an amp of Bicarb, and chase out any unnecessary crystalloid. It’s preemptively aggressive I agree, but I prefer that path to seeing a Hgb of 6.0 gm/dl or so- as my first picture of the bypass run, and the initial CDI readings come to bear.

To hesitate is basically playing roulette. That is just my opinion.

Please offer yours ?

Atherosclerotic aorta

The atherosclerotic aorta can present problems during cannulation for CPB, application of clamps, delivery of cardioplegia, construction of proximal anastomoses for coronary artery bypass grafts, or valve replacement or repair. A large multicenter study identified the presence of proximal aortic atherosclerosis as the strongest predictor of stroke. This lends support to the theory that atherosclerotic emboli liberated by surgical manipulation of the aorta cause most strokes after CPB. Risk factors for ascending aortic atherosclerosis include: significant carotid, abdominal aortic, and left main coronary artery atherosclerosis; aortic wall irregularity on ascending aortic angiogram; adhesions between the ascending aorta and its adventitia; pale appearance of the ascending aorta; and minimal bleeding of an aortic stab wound.

In most cases, the surgeon can palpate the aorta at the time of surgery to select a nondiseased section as the site for insertion of the arterial perfusion cannula or proximal anastomoses. Such palpation may be performed before CPB by briefly clamping the superior and inferior venae cavae with straight Satinsky clamps to effect temporary (10- to 12-second) inflow occlusion that will rapidly decrease cardiac ejection and arterial pressure. With lower pressure in the aorta, gentle palpation can be used to assess the quality of the aortic wall to determine the location of disease-free sites for cannulation and placement of the aortic cross-clamp. Preoperative angiogram should also be performed during cardiac catheterization to assess the smoothness of the aortic lumen and detect wall irregularities. Transesophageal echocardiography and/or a sterile epiaortic probe placed directly on the aorta during surgery are used increasingly to visualize the ascending aortic lumen, with the latter approach being more sensitive because of the interposition of the tracheal carina between the esophagus and distal ascending aorta. Culliford et al.suggested routine use of transesophageal echocardiography in all patients over 65 years old to assess the degree of aortic atherosclerosis.

Reference:

(CHAPTER 28: MANAGEMENT OF UNUSUAL PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED IN INITIATING AND MAINTAINING CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS:)

Mechanism of stroke complicating cardiopulmonary bypass surgery.

BACKGROUND:

Stroke is a devastating complication of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery which occurs in 1 to 5% of cases. Strategies to reduce its incidence require a knowledge of the underlying pathology and aetiology. AIMS: To determine the incidence, pathology and aetiology of stroke complicating CPB.

METHODS:

Prospective review of clinical, operative and cranial CT scan findings in all cases of stroke complicating CPB procedures in our institution over an 18 month period.

RESULTS:

Twenty-one (1.6%, 95% CI 0.9-2.3%) cases of stroke were identified from 1336 CPB procedures. Cranial CT scan, performed in all but one patient, was normal in three patients or consistent with ischaemic stroke in 17 patients. There were no cases of haemorrhagic infarction or intracerebral haemorrhage. It was difficult to differentiate embolic and borderzone infarcts in two cases. After considering the clinical, operative and CT scan features together, 12 (57%, 95% CI 36-78%) of the cases were felt to be embolic in origin and nine (43%, 95% CI 22-64%) due to hypoperfusion in a borderzone.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study demonstrates that stroke remains an important complication of CPB procedures with an incidence in our series of 1.6%. The pathologic type of stroke is predominantly ischaemic in nature due to either cerebral embolism or borderzone infarction. Strategies for stroke prevention in patients undergoing CPB should be targeted primarily at these two mechanisms.

Reference:

Australian and New Zealand journal of medicine (1994)

Volume: 24, Issue: 2, Pages: 154-160

PubMed ID: 8042943

Available from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov